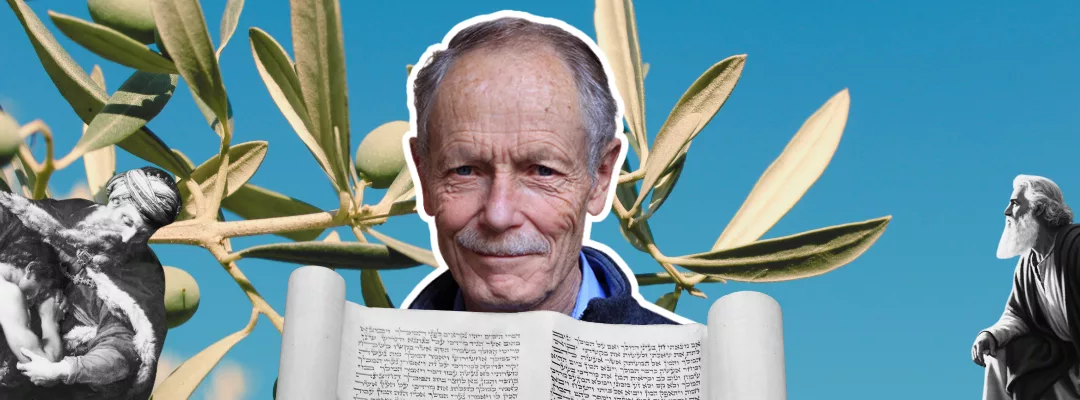

I came across Erri de Luca’s Nocciolo d’oliva (Edizione Messaggero Padova, 2002) in my Fundamental Theology class in my first year (way back in 2021). Our professor discussed this book in its Spanish translation, Hueso de aceituna (Sígueme, 2021) and I wrote this “reaction” paper in response to that discussion. I gave it to him, but he might have lost it along the way or my Spanish may be just that unpolished by that time that he found it hard to read so I never received the feedback.

Anyways, this time I decided to ask my AI secretary to translate my original Spanish work to share it with you now. So, here it comes.

The “Blockages” on Erri de Luca’s Path

In the Premise to his work, Erri de Luca reveals a striking personal practice: he reads the Sacred Scriptures every day. In Hebrew, no less! Here we find a man deeply immersed not only in secular literature but in sacred literature as well. Yet de Luca identifies two fundamental “blockages” that prevent him from crossing the threshold into faith: prayer and forgiveness.

This difficulty, in my view, is not exclusive to de Luca. Many people in our contemporary society share these same hesitations. Moreover, these two realities—prayer and forgiveness—stand at the very center of the Christian (and Jewish) message. De Luca articulates with great clarity why these issues hinder him from becoming a believer.

He perceives it as an attitude of arrogance, almost an impossibility, to address God as a “you.” God is beyond me, He surpasses me; therefore, addressing the Transcendent as though He were my friend, a simple “you” with all its banality and connotations of closeness, as if He were my neighbor, appears bold if not disrespectful. Moreover, de Luca sees in the language of the one who prays in the psalm not only an I–Thou communication but an imperative.

Concerning forgiveness, de Luca looks with reluctance at both the act of forgiving and the fact of being forgiven. He considers his actions something so intimate to him that he cannot rid himself of them, especially his mistakes. If he sets them aside, it is not because of repentance but because of lack of time, aging, etc. For this reason, he cannot accept being forgiven nor can he forgive.

My Responses

On Prayer

Let us begin with prayer, a reality central to the life of the believer. Nearly every religion has some form of prayer. In the Judeo-Christian tradition, prayer has a privileged role: it is the moment in which I communicate with my God.

Communication presupposes relationship. In mythical religions, the relationship between gods and humans is more like that of patron and client. In Judeo-Christianity, the relationship is instead a personal one: filiation.

This is astonishing, even disruptive, to human thought, both in the time of the prophets and in our own. Yet since de Luca already possesses knowledge of the Old Testament—in its original language—our reflection can move more smoothly.

De Luca approaches the divine–human relationship through a distinctly Jewish lens. When he quotes Psalm 16:1, he is unsettled by the boldness of David, who addresses God with an imperative: “Protect me!” He sees a king commanding God, who should be far above him. In response, I would offer de Luca what Christian faith offers the world: the image of Jesus Christ.

We can understand the dynamic between believer and God through Jesus’ own manner of praying. Jesus, a faithful Jew, made prayer a constant part of His earthly life. What do we see in Jesus’ prayer? The relationship between Jesus and God is one of filiation, a Son trusting in His Father. Jesus’ prayer reveals God as a Father, and through Jesus Christ Himself, we have the grace to address God as our Father.

This, of course, is very distinctly Christian. So let us pursue another route, even though for me the first is already sufficient.

Hinneni and Levinas

De Luca notes that the first word preceding every prayer is Hinneni: “Here I am.” I agree. He sees this reality clearly. But hinneni cannot exist on its own; it is not an independent statement but a response. It is not a pure Dasein without alterity. Someone calls me first, and I answer: “Here I am!” Again, prayer presupposes communication, relation, and call.

Here I recall the philosophy of Emmanuel Levinas, a Jewish thinker deeply formed both in the wisdom of Athens and in the faith of Jerusalem. Levinas teaches that when the I encounters the Other, the epiphany of the Other produces a tremor in the world of the I. The I is accustomed to “consuming” everything around it—assimilating everything into itself, that is, totality—but the Other resists this. The Other surpasses me. In the face of the Other, I encounter an ethical imperative: “You shall not kill,” or expressed positively: “Protect me!” Levinas describes the relationship between the I and the trans-cendent Other not as totality but as alterity, characterized by responsibility and expressed in the phrase “Here I am!”—hinneni.

The “trace” of God

I do not intend to offer a full study of Levinas in this small dialogue with Erri de Luca. Instead, I want to highlight one essential insight: the alterity of the Other does not make relationship between him and me impossible. Levinas claims that in the face of the human other we perceive the “trace” of the ultimate Other: God. Thus, the relationship of alterity that I experience with the human other, whom I may still address as “you” even though she surpasses me, reveals—analogically—the possibility of addressing God as You.

The alterity of God does not prevent relationship; it requires it. Hinneni is a response to that invitation. I did not take the first step; God did. He called me by name, as Scripture says. I address Him as “You” not because I deserve to, but because He wills it. Psalm 8 expresses this beautifully: “What is man that You are mindful of him, the son of man that You care for him?”

On Forgiveness

Forgiveness occupies a central place in the Christian message: through His cross and resurrection, Christ brings humanity into reconciliation with the Father. Thus, de Luca’s reluctance about being forgiven and forgiving seems to me very symptomatic of our present time. All of this points to the sense of sin we have today.

With the influence of modern psychology, which seeks to explain human behavior, and various anthropological philosophies, there is a certain reluctance when someone speaks of sin and sinning. We are told to accept our faults as part of our personality. This, to an extent, is healthy. But there is a risk of remaining stuck in acceptance and forgetting the next step: conversion. We justify ourselves by saying that these sins are simply part of who we are and sometimes even define us.

Thus, the possibility of repentance fades. But is forgiveness only about repentance? No. Forgiveness is a gift. A free and undeserved gift from God to humanity. It is not through our effort—though effort is good—but God’s initiative to reconcile us to Himself.

Once more, we return to alterity and relationship. God is a Father offering a gift to His children. What ultimately matters is not the gift itself but the relationship the gift signifies.

Conclusion

I deeply enjoyed this exercise. Erri de Luca pushed me to think and to confront his hesitations—hesitations shared by many people, and yes, at times, even by me. There is a part of me that asks: “How can I be certain He heard me? Can I really address my Creator in such a familiar way? With all the sins I have committed and continue to commit, do I truly deserve His forgiveness?”

I am not sure whether I have expressed myself clearly in this attempt. Perhaps these lines remain the chaos of an unorganized mind. I, too, must clarify within myself the questions raised by de Luca.

Discover more from Tamang Usapan Podcast

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.